Sunday. Dec 8. Little did I think to make entries in my diary so late as this, when it’s nearly a fortnight since our first party left.

Sunday. Dec 8. Little did I think to make entries in my diary so late as this, when it’s nearly a fortnight since our first party left.

This is our state, no parcels are coming into the camp. We are reduced to our last few tins of meat. The German authorities have requested that we do not go into the town to lunch or dine. We have no food rations from the Germans now, for when we were getting our parcels, we had arrangements made that it should be sold to the civilian population. This is a garrison town, and many thousands of German soldiers are expected back on Wednesday or Thursday. They are supposed to be going to take over these barracks, and yet there is no word of our going. We are all fed to the teeth.

Our General (God save the mark!!) who at this rather critical time should be here in our camp, actually on the spot, has in fact taken rooms in a hotel in town, where he spends his days and nights (chiefly in a cabaret called the Germania) with wine and women. Yesterday he had a notice placed on the notice board to say that we should be leaving either Monday or Tuesday probably, and a rumour went round, emanating direct from him, that we were leaving in two parties, one on Sunday night, the other on Monday morning. It proves to be entirely fictitious. He has interviewed the officer for the Repatriation of Prisoners in Eastern Germany, and also the Representative of the Danish Commission for the same, yet he has no news, or if he has, he will not publish it.

Our General (God save the mark!!) who at this rather critical time should be here in our camp, actually on the spot, has in fact taken rooms in a hotel in town, where he spends his days and nights (chiefly in a cabaret called the Germania) with wine and women. Yesterday he had a notice placed on the notice board to say that we should be leaving either Monday or Tuesday probably, and a rumour went round, emanating direct from him, that we were leaving in two parties, one on Sunday night, the other on Monday morning. It proves to be entirely fictitious. He has interviewed the officer for the Repatriation of Prisoners in Eastern Germany, and also the Representative of the Danish Commission for the same, yet he has no news, or if he has, he will not publish it.

Officers were stopped by a German Patrol late on Thursday and requested to give up their walking-sticks. On their refusal a disturbance was made and several civilians became very hostile. Seeing the menacing look of the crowd some officers gave up their sticks, and others broke them and threw them at them. All the action the General has taken in the matter is to publish a notice that officers to not carry sticks in the town and to state that ‹the German authorities regret the disturbances between English officers and German soldiers and civilians and request that, in view of the existing circumstances, no notice be taken of the incident›.

An officer, a Captain Greg was noticed to be missing about three days by his room companions, who became rather anxious about him. One night a woman came out of a house and shoved a note into the hands of a passing officer. It was to the effect that Greg had been enticed into, or had somehow entered into a house, and set upon by several ruffians, who placed him hors de combat, with several broken bones. Six of our fellows went down, got him out and took him to hospital.

The Danish Committee have advised us to hand them our surplus stocks of foods when we go. Comic idea of how much food we’ve got they seem to have. Today Whittaker, the Camp Adjutant, a Guards Captain and a boy of about 21, nearly as big a twinnick as the General, wired to Danzig to say ‹470 British Officers & men at Graudenz without food›. Might have some effect. Our fleet is supposed to be cruising about in the Baltic.

The Danish Committee have advised us to hand them our surplus stocks of foods when we go. Comic idea of how much food we’ve got they seem to have. Today Whittaker, the Camp Adjutant, a Guards Captain and a boy of about 21, nearly as big a twinnick as the General, wired to Danzig to say ‹470 British Officers & men at Graudenz without food›. Might have some effect. Our fleet is supposed to be cruising about in the Baltic.

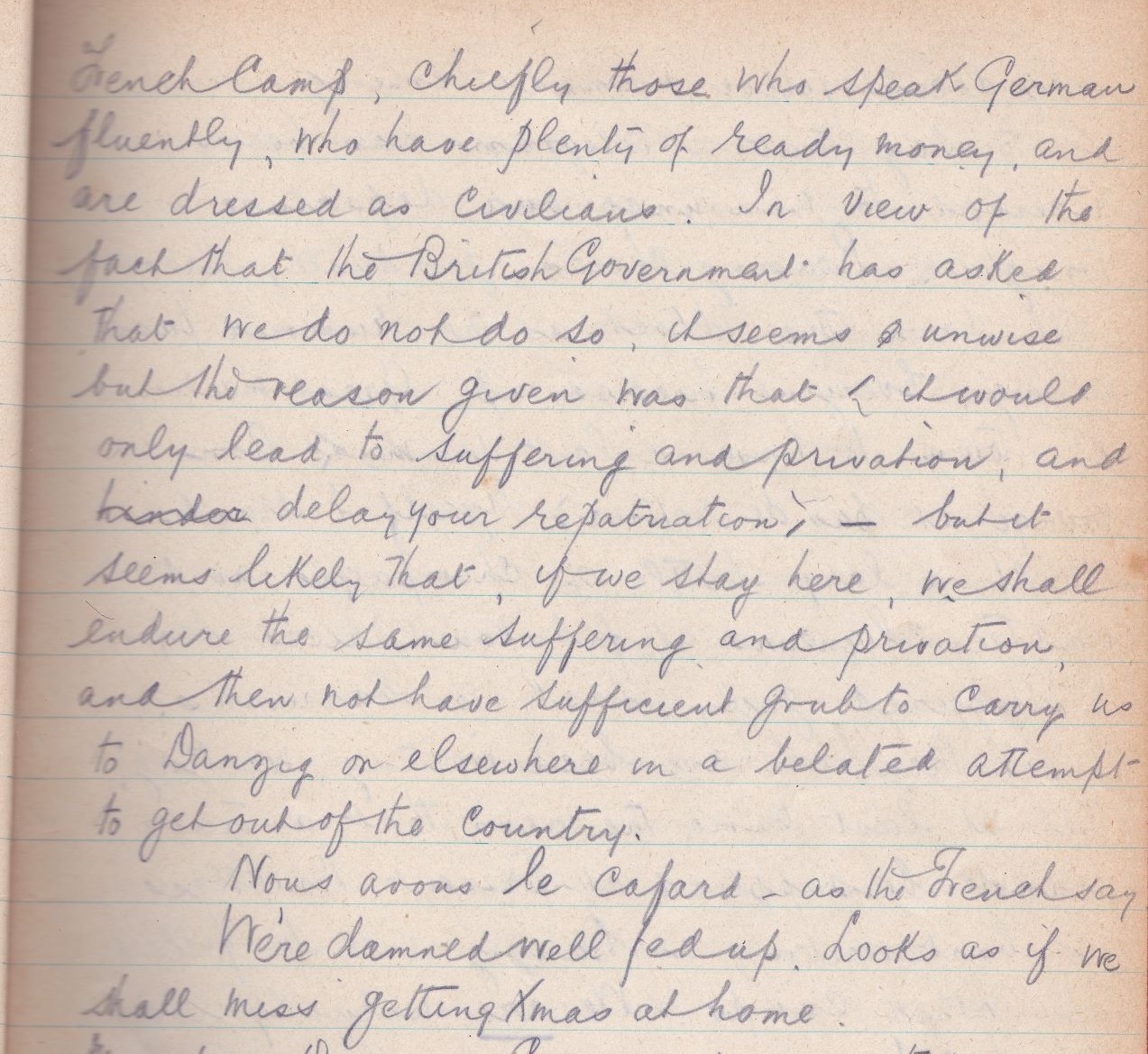

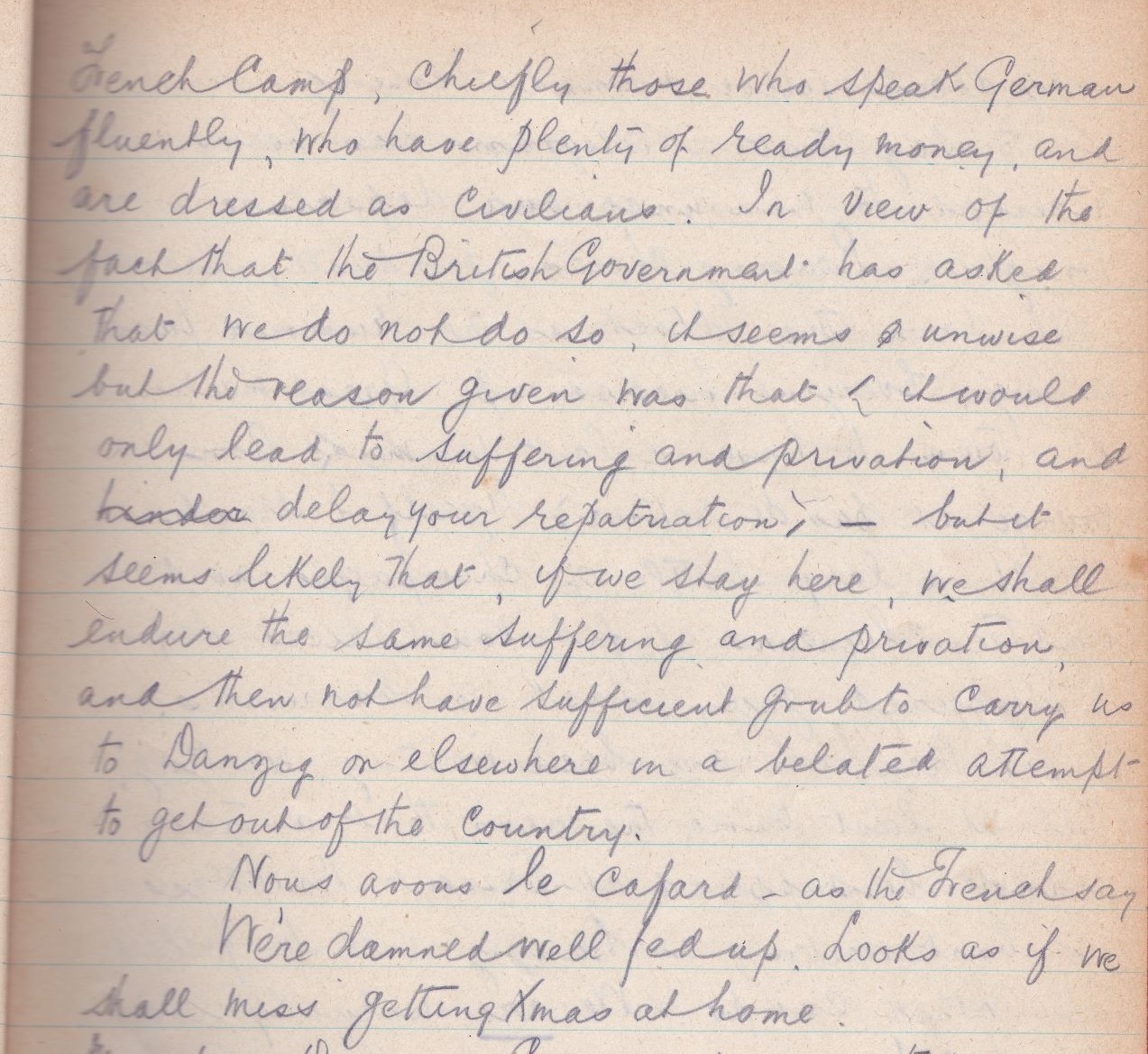

An alphabetical roll call was called this morning. Seven people were missing. No one knows whether they are in the town, or have tried to get off to Danzig on their own. Several Frenchmen have left the French Camp, chiefly those who speak German fluently, who have plenty of ready money, and are dressed as civilians. In view of the fact that the British Government has asked that we do not do so, it seems unwise but the reason given was that ‹it would only lead to suffering and privation, and delay your repatriation› – but it seems likely that, if we stay here, we shall endure the same suffering and privation, and then not have sufficient grub to carry us to Danzig or elsewhere in a belated attempt to get out of the country.

Nous avons le cafard – as the French say.

We’re damned well fed up. Looks as if we shall miss getting Xmas at home.

Thursday. Dec 12th. Went into town all day with Miller. Fearful getting up this morning. Thousands of degrees of frost. Had lunch in town, went to a comfortable Weinstuber, read and drank liqueurs all the afternoon. Dined in town. Was visited in the evening by the Naval Officer, a doctor who gave us ripping and recent news of England. Felt no end cheered. Stayed up till two o’clock stewing in front of the fire and reading.

Thursday. Dec 12th. Went into town all day with Miller. Fearful getting up this morning. Thousands of degrees of frost. Had lunch in town, went to a comfortable Weinstuber, read and drank liqueurs all the afternoon. Dined in town. Was visited in the evening by the Naval Officer, a doctor who gave us ripping and recent news of England. Felt no end cheered. Stayed up till two o’clock stewing in front of the fire and reading.

Wednesday. Dec 11th

Wednesday. Dec 11th

Tuesday. Dec 10

Tuesday. Dec 10 Monday. Dec. 9.

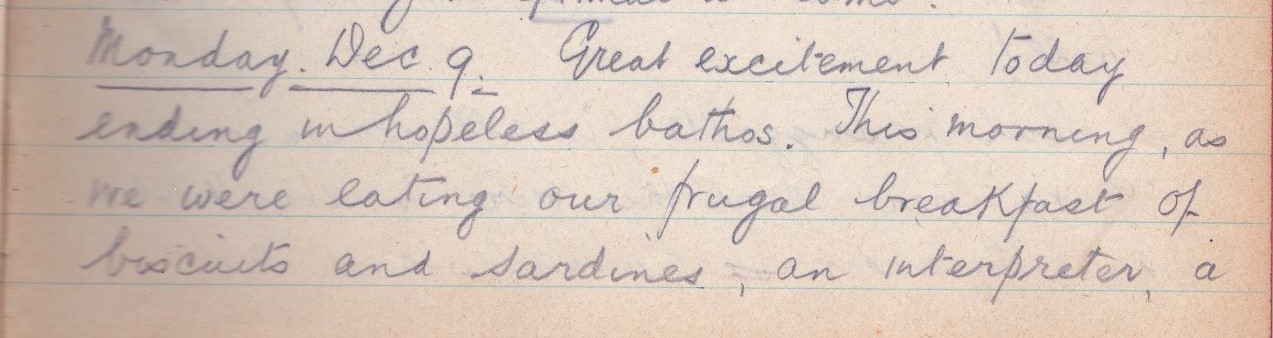

Monday. Dec. 9.

Sunday. Dec 8.

Sunday. Dec 8. Our General (

Our General (

The Danish Committee have advised us to hand them our surplus stocks of foods when we go. Comic idea of how much food we’ve got they seem to have. Today Whittaker, the Camp Adjutant, a Guards Captain and a boy of about 21, nearly as big a twinnick as the General, wired to Danzig to say ‹470 British Officers & men at Graudenz without food›. Might have some effect. Our fleet is supposed to be cruising about in the Baltic.

The Danish Committee have advised us to hand them our surplus stocks of foods when we go. Comic idea of how much food we’ve got they seem to have. Today Whittaker, the Camp Adjutant, a Guards Captain and a boy of about 21, nearly as big a twinnick as the General, wired to Danzig to say ‹470 British Officers & men at Graudenz without food›. Might have some effect. Our fleet is supposed to be cruising about in the Baltic.

Another was simply thin rope plaited into a kind of thick tyre.

Another was simply thin rope plaited into a kind of thick tyre.

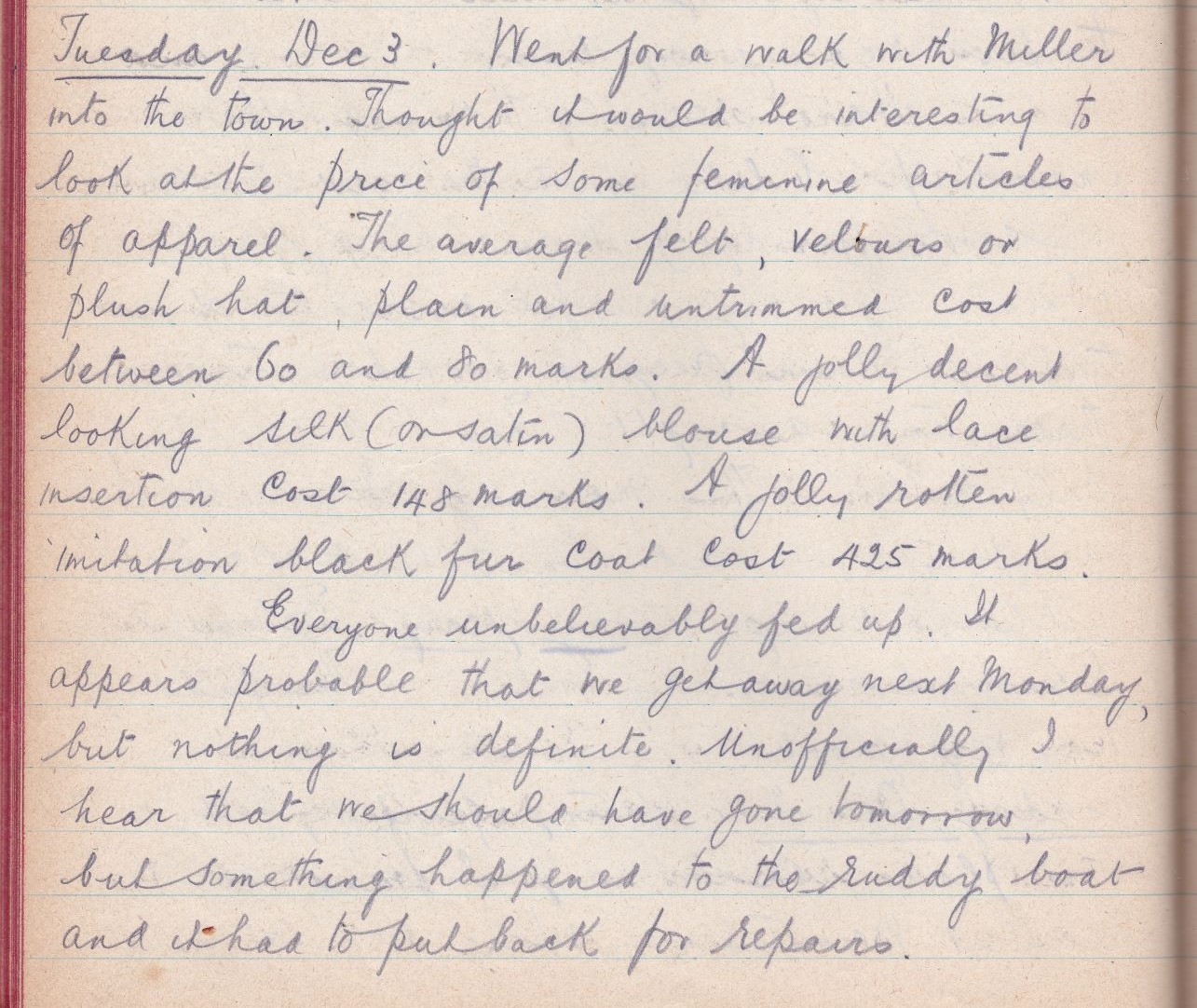

Tuesday. Dec 3

Tuesday. Dec 3